Kinship and long-distance genetic networks in Early Bronze Age Lower Austria

Early Bronze Age Social Structure & Kinship in Lower Austria

The article takes the reader into the farmsteads and graveyards of Early Bronze Age Lower Austria, north and south of the Danube, to explore how people lived, married, moved and were buried. By combining archaeology with ancient DNA, it reconstructs real families and traces how men and women were woven into wider regional networks.

When we read about vanished civilizations, it’s easy to forget that their descendants still walk among us. If you’re curious which of them you might share roots with, you can explore your own genetic links at www.mytrueancestry.com.

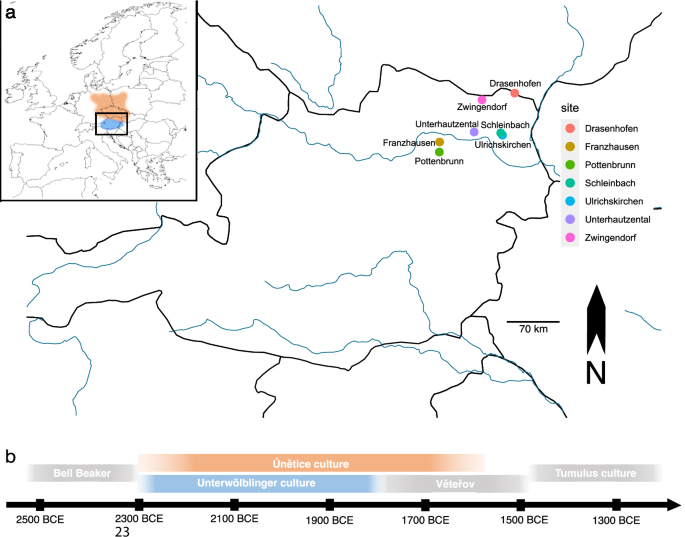

The study focuses on a compact region about 80 kilometres across, yet divided culturally and genetically by the Danube River. North of the Danube lay the Únětice communities, connected to the broader cultural world that produced the famous Nebra Sky Disc and the princely barrows of central Germany. Here, small farmsteads dotted the landscape with modest cemeteries tucked nearby, where the dead were buried in reused storage pits and family plots close to the living.

South of the river stretched the territories of the Unterwölbling groups, culturally linked to communities in southern Germany. Their world was marked by vast cemeteries like Franzhausen I and Pottenbrunn, containing hundreds or thousands of carefully arranged graves that followed strict gender-based burial customs inherited from Bell Beaker traditions.

Across both regions, the dead were usually buried in a flexed position, lying on their side and facing east, as if turned towards the rising sun. Yet the details of grave orientation and treatment of men and women differ strikingly between the two cultural zones.

At sites such as Drasenhofen, Zwingendorf, Unterhautzenthal, Schleinbach and Ulrichskirchen, the article describes small cemeteries near farmsteads. Most graves held a single individual, although double and multiple burials are also present. These group burials offer precious opportunities to reconstruct genealogies using ancient DNA, with family trees extending across three generations.

Men and women were commonly buried in similar fashion: usually on their right side, heads to the south, faces turned eastward. This shared posture emphasized a common way of entering the afterlife rather than hammering home strict gender divisions. The similarity in burial treatment reflects a society where gender roles, while present, were not rigidly materialized in death.

Grave goods are generally modest, reflecting a world of smallholders rather than bronze princes. Typical offerings included bone and shell ornaments, small bronze dress fittings like pins and rings, and pottery bowls or jugs placed carefully by the body. Tools and weapons such as daggers appeared only rarely. Food offerings survived as scattered animal bones and charred plant remains, suggesting shared meals that connected the living with the dead.

This is a world of small-scale farmers rather than bronze princes, but the genomes and burials together reveal a tightly knit countryside of long-lasting families and local ties. Using DNA analysis, researchers reconstructed family trees within cemeteries, showing that men were often buried alongside their fathers and sons, reinforcing patrilocal inheritance patterns where farmsteads and land passed down the male line.

South of the river, at major cemeteries such as Franzhausen I and Pottenbrunn, the article moves into a very different world. Here, hundreds even thousands of burials have been uncovered, often with clear signs of social ranking. Single burials dominated, with double and multiple burials extremely rare, making the occasional triple grave particularly significant.

Following Bell Beaker tradition, graves are strongly gendered with systematic differences in body positioning. Men and boys were usually placed on their left side with heads to the north, while women and girls lay on their right side with heads to the south. Both faced east toward the rising sun, creating a neat, almost diagrammatic male-female pairing that was considered important enough to observe even for young children.

This pattern holds even for children, showing that communities cared about marking boys and girls as gendered beings already in death. Grave depth and the amount and quality of goods vary, hinting at different social status, though repeated reopening of graves and removal of goods sometimes obscures the full picture. The surviving evidence suggests marked social differences, with some graves containing elaborate ornaments and higher quality items.

Double and multiple burials are rare in these large cemeteries, which makes the occasional triple grave, such as one at Franzhausen, particularly striking. This unusual burial contained an adult man and two adolescent boys, with DNA revealing that one boy was the man's biological son while the other showed no close genetic relationship, raising questions about fosterage, household composition, and social bonds beyond blood kinship.

Despite their proximity, the article shows that people north and south of the Danube did not share exactly the same ancestry. The genetic analysis reveals two distinct ancestral balances that align remarkably with the cultural divide marked by the river.

North of the Danube, Únětice individuals carried a stronger proportion of steppe-related ancestry, linking them to pastoralists from the distant grasslands north of the Black and Caspian Seas. When their DNA is compared to earlier European populations, it sits closer to these mobile herders, with steppe-related ancestry roughly twice as strong as early farmer ancestry. This reflects centuries of migration and mixture, where people with steppe ancestry had moved into central Europe and intermarried with local farming communities.

South of the Danube, Unterwölbling people showed the reverse pattern, carrying more early farmer ancestry connected to the very first agricultural communities that spread from Anatolia into Europe millennia before. Their genetic signature digs more deeply into Europe's older farming past, while steppe-related ancestry remains relatively lower.

This is not a simple picture of one blended population. Instead, it suggests that different communities built different networks of marriage and exchange, drawing more heavily on one or another ancestral stream. The river valley that today can be crossed in minutes once marked the edge between communities whose origins and family histories had been shaped by very different proportions of steppe migrants and long-established farming populations.

By piecing together Y-chromosome lineages (inherited through the male line) and mitochondrial lineages (inherited through the female line), the article reconstructs family trees at several cemeteries, extending in some cases across three generations. These genealogies reveal clear patterns of residence and marriage.

The genetic evidence shows that men typically remained in their birth communities throughout their lives. Y-chromosome lineages cluster within individual cemeteries, and men are frequently buried alongside their fathers, sons, and brothers. This patrilocal pattern suggests that farmsteads, land rights, and burial plots passed down through male lines, creating stable cores of related men in each settlement.

Women show a different pattern, with greater genetic diversity in mitochondrial lineages within individual sites. This suggests that many women moved away from their birth communities upon marriage, joining their husbands' families and eventually being buried in their adopted communities' cemeteries. The pattern fits with female exogamy, where women serve as marriage partners linking different local groups.

Network analysis of genetic links (Identity-by-Descent, which detects shared DNA segments passed down from common ancestors) further supports this picture. In the Únětice group, men tend to have slightly more connections within their own sites than women, hinting at male-centered local networks that maintained stronger internal genetic cohesion over generations.

Earlier work on Central European Bronze Age cemeteries highlighted strong patterns of female exogamy, where women leave their birth community to marry elsewhere. The article finds that this was broadly true, but not the whole story. The genetic and burial evidence reveals more complex patterns that challenge simple models of rigid female mobility.

In the Únětice north of the Danube, two particularly intriguing cases appear at Drasenhofen: adult women of reproductive age are buried alongside their fathers or brothers, and in some cases also their own children and grandchildren. These women also show genetic links to later descendants in the same cemetery, suggesting that at least some female lines could be anchored locally over generations.

These "homecoming" women challenge the notion of rigid female exogamy. They might represent daughters who did not leave at all, wives who returned after marriage, or other more complex marital and social arrangements. Perhaps some women inherited property rights, maintained strong natal family ties, or negotiated marriages that allowed them to remain close to their birth families. The article underlines that burial places do not always map perfectly onto where people actually lived, but they do capture how families and communities chose to remember and group their dead.

At Drasenhofen, one family reconstruction hints at even more subtle networks: two brothers share the same father but have different mothers, and closer inspection of their X-chromosome DNA suggests that their mothers were themselves distantly related. This indicates that women may have come from the same wider region or long-standing marriage network, revealing how female lines could circulate within stable patterns over generations rather than representing completely random exchanges between distant communities.

The genetic links in this study are not confined to the Danube corridor. The article tracks shared DNA segments between individuals in Lower Austria and other Bronze Age populations across Central Europe, revealing surprising long-distance ties that illuminate the continent-spanning networks of the Bronze Age world.

Individuals from both Únětice and Unterwölbling communities share many long DNA segments with people from the Lech valley in southern Germany, especially in the Middle Bronze Age. This suggests that, by that time, people with ancestry rooted in Early Bronze Age Austria were central to the population of the Lech region. The connection is particularly unexpected because the Middle Bronze Age Lech Valley population was previously thought to represent new arrivals around 1700 BCE, yet the genetic links show continuity with earlier Danubian communities.

Unterwölbling individuals show strong connections to an Early Bronze Age double burial at Bad Zurzach in what is now northern Switzerland. This signals ties to communities far to the west, likely linked along the Danube and its tributaries. The shared DNA segments suggest ongoing relationships between Lower Austrian families and Swiss communities, perhaps maintained through generations of marriages, fosterings, and movements along river routes.

These networks did not require entire families to pack up and move. Rather, repeated marriages and exchanges over generations could knit communities together across hundreds of kilometres. The article emphasizes that the Danube functioned as a great Bronze Age corridor of people, objects and ideas a "sheet bronze" highway that carried not just metal objects and trade goods, but real kinship ties between distant communities.

The article opens a particularly vivid window onto childhood in Early Bronze Age Lower Austria, showing that life for the youngest members of society was often short, painful and precarious. The combination of bone analysis with ancient DNA allows researchers to follow real children and their families through disease, injury and early death.

One of the most striking stories comes from Unterhautzenthal, where archaeologists uncovered several related toddlers from the same family who died in rapid succession. Ancient DNA confirmed their close kinship ties, while osteological analysis revealed the harsh realities of their short lives. The children's bones bear clear marks of serious illness, including meningitis (infection of the protective membranes around the brain and spinal cord) and pleural infection (inflammation around the lungs). These conditions leave characteristic changes on bone surfaces, allowing specialists to diagnose them thousands of years later.

At Schleinbach, the evidence takes a darker turn with a case of apparent child murder. The burial of this young individual showed clear signs of deliberate killing, with fatal injuries recorded in the bones. This was not an accident or battlefield death, but a targeted act of violence against a vulnerable child. When set alongside the diseased toddlers of Unterhautzenthal, the case suggests that suffering in early life came not only from harsh living conditions and disease, but sometimes from violence within the community itself.

Despite these tragedies, children were carefully integrated into community burial practices. Across the farmstead cemeteries north of the Danube, children were usually buried in the same crouched position as adults, with heads to the south and faces turned eastward. Their graves typically contained modest offerings: small pottery bowls, bone or shell beads, and occasionally simple bronze ornaments. South of the Danube, even young children were subject to strict gender-based burial rules, with boys and girls positioned according to the same male-female binary applied to adults.

One of the most vivid cases discussed is the triple burial at Franzhausen in the Unterwölbling area. The grave contains an adult man and two adolescent boys, with DNA showing that one boy is the man's biological son a direct father-son pair. The second boy, however, is not closely related to them despite being buried in the same grave. He shares only very distant genetic links to the Únětice north of the Danube, well beyond the eighth degree of kinship.

This adolescent outsider, placed in death with a father and son, raises questions that illuminate the complexity of Bronze Age households: was he a foster child, a servant, a war companion, or someone joined to the household by social bonds rather than blood ties? His presence suggests that belonging could be defined as much by social relationships and shared experiences as by genetic kinship, and that Bronze Age families might incorporate non-relatives into their most intimate burial spaces.

The genetic evidence reveals that Bronze Age communities were far more interconnected than their quiet farmstead settings might suggest. Rather than isolated agricultural settlements, these Danubian communities participated in continent-spanning networks of kinship and exchange. The strongest genetic connections do not follow the shortest geographic distances, but instead cluster along major river routes, particularly the Danube corridor and connections to the Lech Valley and Bad Zurzach.

This pattern suggests that Bronze Age people preferred particular routes especially major rivers for maintaining contacts, moving metal objects, transmitting ideas, and arranging marriages. The genetic data place real, flesh-and-blood kin within what archaeologists have called the "Danubian sheet-bronze network," a belt of communities tied together by thin hammered bronze objects and shared styles.

Discover how your DNA connects to ancient civilizations at www.mytrueancestry.com.

Comments